Our Story

Six Observations

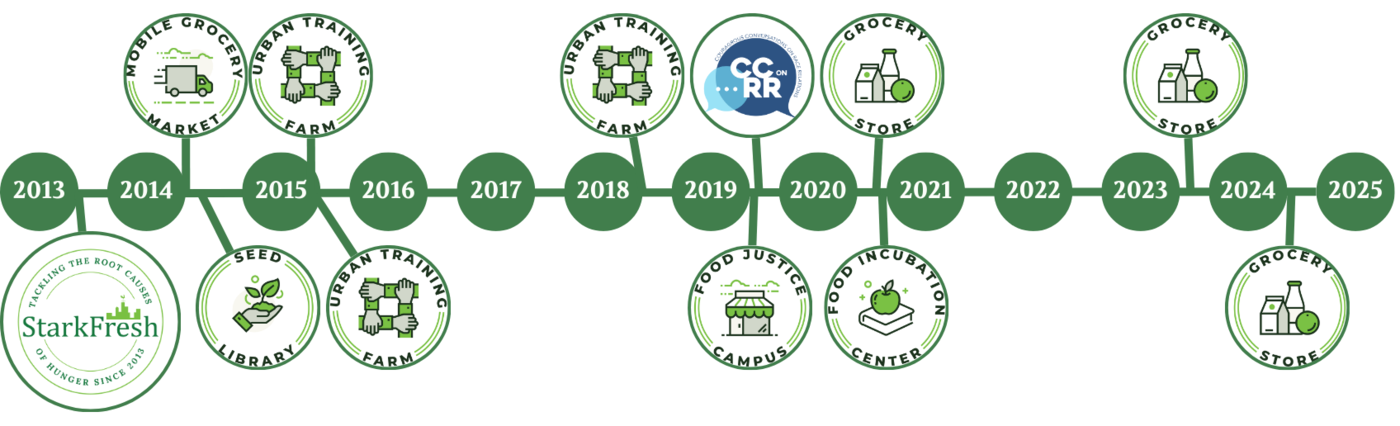

Our nonprofit has been operating since 1983 in various community-development roles. In 2013 we took the name StarkFresh when we shifted our focus toward fighting hunger throughout Stark County, Ohio.

Our efforts to fulfill this mission have been rooted in six key observations.

First Observation:

Hunger is a major problem in Stark County.

Stark County has large groups of individuals without continuous access to nutritious, affordable meals.

One of the results of this is rampant food insecurity, where individuals are unsure when or if they will be eating their next meal.

In Stark County, OH, roughly 15% (53,880) of all residents and 21% of all children (17,190) fall into this category.

According to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), being food insecure means lacking reliable access to a sufficient quantity of affordable, nutritious food.

The USDA defines food insecurity as a state in which "consistent access to adequate food is limited by a lack of money and other resources at times during the year."

Studies have proven that a lack of adequate nutrition affects physical and mental health, life expectancy, the ability to maintain employment, as well as the capacity for learning in school.

Second Observation:

Barriers prevent access to affordable, nutritious food.

Many people in Canton and throughout Stark County have little to no access to establishments offering affordable, nutrient-dense foods for sale, which has caused terrible health consequences in our communities.

In Stark County, 12.9% of all adults aged 20 and above have been diagnosed with diabetes.

Many of the affected live in an area best described as a Food Apartheid (a more accurate term for what some call ‘food deserts), or near a Food Swamp.

The USDA defines a food desert as a location where an individual lives more than one mile from a grocery store offering healthy food.

Food Apartheid better describes this phenomenon because these are not desolate, empty neighborhoods; but rather neighborhoods whose overwhelming majority of residents are persons of color. It is no accident that this is true; residents of these communities have been deemed unworthy of the right to access nutritious food, and whole communities are being geographically and economically isolated from healthy food options.

Food Swamps are geographic areas with a high density of establishments that sell high-calorie fast food (or junk food). Instead of having access to supermarkets or grocery stores for their food needs, many community members have no food access or are served only by fast-food restaurants and convenience stores that offer few healthy and affordable food options.

This lack of access to healthy food contributes to a poor diet and higher levels of obesity and other diet-related conditions, such as diabetes and heart disease.

Third Observation:

Many of our county’s residents lack the skills to feed themselves well.

There are notable (and unfortunate) differences between today's meals and those that our ancestors ate.

Most people today do not know how to grow their own food, and many do not understand how the food they consume is produced.

To compound the problem, the number of people who are recipe or cookbook literate (able to decipher and follow recipes) keeps falling every year, creating another barrier to consuming the nutrient-dense foods that humans use to prepare for themselves. In short, if a recipe uses terminology or techniques unfamiliar to the reader, it is useless, preventing them from experiencing the joy (and positive health outcomes) that can come from cooking and eating their own food. Now generations of individuals have never learned how to read and understand a recipe.

Tackling the persistent and widespread problems of food insecurity and poor nutrition means helping people learn the skills our ancestors knew very well—how to create "made from scratch" meals at home.

Fourth Observation:

Education AND Access Matter

A person can learn the fundamentals of cooking and become cookbook literate but still lack access to the tools and utensils that those recipes require to make a meal.

Providing people with ingredients and recipe cards is not enough to fight hunger.

It is far more effective to teach people simple, straightforward ways to make meals using the items and cooking knowledge they already possess.

Fifth Observation:

Hunger is increasing despite all those organizations that fight it.

As the average income of people in need continues to decrease, poverty levels continue to rise.

Many area agencies claim to be "fighting hunger."

Yet, as their budgets increase year-to-year, so do the number of people relying on their services.

On the surface, it appears that these area agencies are failing to address hunger's root causes. However, a deeper look into the data outlines a more realistic picture of what is going on.

Though Stark County's poverty rates have decreased over the past several years—including in cities like Canton—specific areas with high concentrations of poverty continue to worsen. For example, in Canton, 49.8% of the residents under 18 are living in poverty.

Sixth Observation:

Poverty leads to hunger and poor health.

The total number of people living at or below the poverty line is staggering throughout our region, especially in areas such as Canton, OH, where 31.8% (22,948) of residents fall into that category.

There is an undeniable connection between poverty, poor health, and issues of hunger.

Stark County's data indicates that 13% of Canton's population (8,579 residents) live in areas with the highest concentrations of food insecurity, poverty, and severe health problems.

Among these residents, 69.4% earn less than $34,000 annually, and 56.5% of households earn less than $24,000 per year.

Although Canton is overwhelmingly white (65.9%), its black and multiracial residents (29.8%) are disproportionately affected by poverty.

Among Canton’s residents living in poverty, 45.45% are black or multiracial, and only 25.55% are white. Statistics prove that being born and growing up as a black or multiracial person means you are far more likely to live in poverty than your white peers.

Poverty tends to be multi-generational, so being born into poverty often means experiencing poverty throughout one’s lifespan.

From these six initial observations arose six questions:

1. How could we deliver the promise of affordable, nutrient-dense groceries to neighborhoods in need?

2. How could we overcome a system designed over decades to keep people in poverty?

3. Is there a way to reduce people’s barriers to growing their food?

4. How could we increase “cookbook literacy” and remove the physical and knowledge barriers preventing people from cooking their food?

5. How could people be expected to consume better food if they do not have the know-how to prepare it themselves?

6. Can meaningful, well-paying local food and agriculture careers be created to combat poverty and employment barriers?

StarkFresh was formed as a way to address these questions.

When we transitioned fully into StarkFresh, our organization remained small, allowing us the flexibility to find out what the community truly needed and which approaches would be most effective.

We regularly adapt and change our programming to increase our overall community impact.

As we grow and listen to the needs of local residents, StarkFresh's approach continues to evolve to reflect our organization's effort to make a meaningful impact on the community.